What Attention HORs are FOR

Carruthers in his “The evolution of consciousness” (2000) attempts to produce a “successful explanatory account of p-consciousness” (p256) through Higher Order Relations (HORs) in order to bolster the case against mysterianism. Relying on other works to form the negative argument against mysterianism, Carruthers presents his dispositionalist HOT argument as an alternative account to fill the void created by undermining the mysterianist position.

The “Phenomenal Consciousness” – p-consciousness – that Carruthers attempts to account for is the inner-sense of what-it-is-like-to. This contrasts with those phenomenal experiences which one is not aware of. At the p-conscious level there are many sensory experiences that we are not attending to, the feel of the seat that you are sitting on, that itch you have in the middle of your back, the sound of the ticking of the clock.

To deal with the supposition that p-consciousness is developed out of First Order Relations (FORs) Carruthers relies upon “Trilemma for FOR Theory” argument (2000b p168-179) loosely this involves the argument that some experiences are conscious, and others are non-conscious, and it is hard to explain non-conscious experiences in first order terms, therefore FOR theories cannot have full explanatory power for p-consciousness. Consequently, if FOR leaves us wanting, we need a HOR.

HORs (Higher Order Relations) come three different ways. Broadly speaking, HORs if they are not HOT (Higher Order Thoughts), they’re HOEs (Higher Order Experiences). Though some HORs are HODs – versions of Dennet’s Higher Order Descriptivism (HODs) – but Carruthers will go on to argue convincingly that HODs are merely part of the subset of HORs that are HOT.

HOEs emerge from an ‘inner sense’ – an internal scanner that binds together the inputs of our various senses and it is this inner sense that develops into our phenomenally experienced p-consciousness.

In contrast, under HOT theories p-consciousness emerges where a “perpetual state is, or can be, targeted by an appropriate HOT”. Amongst these theories there are two sub-categories:

- there are actualised HOTs – situations where p-consciousness is a function of the fact that each perceptual state is accompanied by a HOT, and

- in contrast there is Carruthers’ preferred view, the dispositionalist one, where the potentiality of the availability of a HOT determines the p-consciousness of the experience of that percept – where a percept is a datum which is available to consciousness.

Finally there the HODs which don’t seem to be in the game at all. HODs are linguistically-formulated descriptions of the subject’s mental states. In section 8 of Carruthers (2000) he holds that everything a HOD can do, a HOT HOR can do, and more. Dennet’s HODs are, according to Carruthers, functions of the language of thought, which is itself an emergent reaction to the development of ‘inter-personal communication’, to argue that HOTs can predate HODs Carruthers posits that ‘structured HORs’ can emerge independent of language, for which he relies on the examples of:

- deaf people without specific tutoring in sign languages who develop their own means of communicating their intent through gesture, and

- the existence of intentionality in those who are a-grammatically aphasic, who are, under experimental conditions, capable of acting as though they hold propositional attitudes: where they act as those they believe that “A believes that P”, even though they cannot verbalise this.

Of these examples the aphasics hold the greater weight, I believe. Presumably some people were interacting with those deaf people who were reared outside of the deaf community and away from books, and it is not difficult to see how some dialect of gestural communication, however inelegant, could emerge under such circumstances. Furthermore if gestures can be conceived as words, in the same manner as pictures, blots of ink, or sounds can be conceived of as words, then it is not hard to imagine how an internal structured language could occur. While they may have a limited vocabulary, and a poor capacity for expression these people are not of a type which is other than ourselves, they are merely badly educated.

With the aphasics however there is an inability to comprehend sentences, and an inability to create sentences, which suggests that their capacity to infer information not directly perceptually accessible to them would require a means of thinking about the scenario which uses abstractions other than words, therefore “explicit natural language grammar and resultant natural language propositions” (Varley 2000 p145) are not necessary for coming to correct inferences in Sally/Anne tests and the like, in which case Dennet’s HODs are of very limited explanatory value.

We can grant that Carruthers is correct in this argument, HOD’s are HOT, just of a certain form, but the status of HOTs is unfortunately vulnerable, if what Carruthers is correct in what he holds to be true.

In developing his dispositionalist HOT argument Carruthers also attempts to undermine the utility of other HOR arguments so that the anti-mysterianist position is congruent with his dispositionalist HOT argument.

For Carruthers there are three pre-requisites to successfully emergent p-consciousness under the dispositionalist HOT model, firstly there is “the evolution of systems which generate integrated first-order sensory representations available to conceptualised though and reasoning” conjoint with this there is a “special-purpose short-term memory store” (Carruthers 2000 p266) then finally there is the parallel development of a faculty which is capable of managing intensionalist Theory-of-Mind (ToM) relationships. The intuition being that the ToM mechanics – which allow for the comprehension of relations between people – can be applied to conceptual experiences then. If so, then a bootstrapping event could have occurred circa 100k years ago where these processes could have been interlinked thereby allowing modern humans, as distinct from merely biological humans, to stride out upon the world like new gods, presumably to murder the old ones soon after.

If this is to be a successful story of p-consciousness crystallising into being, then it does not succeed tremendously well. To begin with, brain real estate is expensive, a “special purpose short term memory store” would have had to evolve, and while there are no costs to me, a male, having redundant nipples, developing new brain architecture just at that point where I decide how I interact with the world seems to be a peculiarly risky proposition. There are so many ways for this to go wrong, and no way for it to be of benefit, until that moment where the ToM faculty invades it and spontaneously causing p-consciousness to emerge. As stories go, it is as unlikely as a species of dinosaur randomly evolving wings and feathers discovering that it is a bird that can fly only after it has been chased off a cliff.

The next issue is that if this were a unique feature of the brain, then it would be relatively easy to find. The great difficulty in brain exploration is that everything interacts together all of the time, the weakness in the statistics of brain imaging is not simply a function of low powered studies, it is also that most brain states – as opposed to subjective mental states – appear to be relatively similar, in a highly complex way, when examined with the tools that we use to examine them.

Finding somewhere that only gets used when HOTs are present, or potentially present, and as a consequence allows the emergence of p-consciousness to occur ought to be relatively simple, but there is little about the brain that is relatively simple.

There is also the need, under this model, for perceptual states to have developed independently from relational ToM – as though there was a specific part of the brain which is used to consider social relationships. There are models that suggest that there is such a locus of function, but these tend to be almost as broad as the brain itself, consider figure (A) above from Völlm et al. (2006). In this experiment Völlm et al. have attempted to identify those areas of the brain which are active when ToM is being considered and which are also active when we empathise with the emotional state of another.

Presumably not all parts of the brain that are active when we are engaged in intensional tasks are engaged when we are empathising, consequently these findings are minima for ToM functional loci, even these minima seem to be widely distributed and wholly integrated across the brain. Dunbar (1989) meanwhile argues that the purpose of the entire neo-cortex it to facilitate our management of social relationships with language being an emergent behaviour that developed to allow us to manage the tensions and co-ordinate the activities of our large social groups. The proposal that such large co-ordinated parts of the brain may have only stumbled upon the resting potentiality of a “special purpose short-term memory store” long after the biological capacity had evolved, and only did so once, seems a stretch of the imagination that is reckless to take.

Positing that there existed an organisational, though not structural, Chinese wall between large sections of the brain which has now been subsumed under the universal utility of the p-conscious experience is another form of mysterianism.

Consider the semantic mapping in the figure (B) to the right. Subjects were shown natural videos where they were gives tasks (finding vehicles, or people) or were allowed to watch without being under direction.

Those parts of the brain which were activated or suppressed when the video showed a particular object under each of these tasks were mapped (Huth et al. 2012) and does suggest that there exists a strong correspondence between the semantic organisation tree used by the project and the patterns of activation/suppression in the subjects.

If there exists relational organisational structure at a level below interpersonal relations then Carruthers’ argument for dispositional HOTs is under a great deal of pressure, as it would seem to be that they are not adding the special ingredient of ‘relations’ to the perceptual states that exist in the brain already.

If you go to http://gallantlab.org/brainviewer/cukuretal2013/ it will let you play with this representation of the brain and you’ll find that almost any randomly selected part of the brain will exhibit a pattern of activation/suppression that maps reasonably onto the semantic web in the study which is derived independently from Princeton’s WordNet graph.

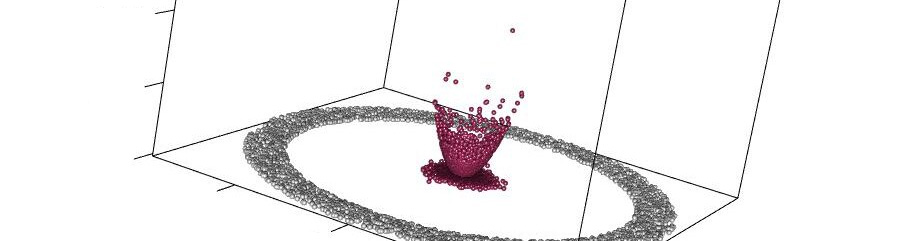

In Figure (C) above, I selected a point within the left posterior Superior Temporal Sulcus (pSTS) The section on the right in Figure (C) shows those the activation/suppression mapping for that particular point when the subjects were viewing video that contained the relevant object, where red is activation and blue is suppression, and the size of the dot is related to the magnitude of the effect.

The most significant aspect is that there is clustering between related concepts. What this particular instance of clustering represents is probably not meaningful, but it does show that there is a concept driven relational mapping that exists within the brain. This particular clustering pattern is likely to be unique, but it is relatively difficult to discover parts of the brain which show a pattern of activation that does not seem to be semantically organised.

Across the brain as a whole it is hard to see what the overall pattern is, and for any large area that seems to be associated with a particular branch of the semantic tree, at the voxel level there’ll be parts of that area which show seemingly unrelated patterns of activation. To generalise, the semantic map of the brain seems to be strikingly complicated, but at the lowest levels available to us there seems to be systems of activation which are driven by conceptual relationships.

This does not look like how Carruthers suggests that the brain might look, it looks more like relational association is the most fundamental form of organisation, where like is associated with like.

This difficulty for Carruthers would be useful to the mysterians had Carruthers’ arguments against HOEs been so week. The primary assertion against HOEs is that to develop them, one would need HOTs, and if one had HOTs then one would not need HOEs, but this is based on a particular view of simulation.

HOEs, Carruthers says the simulationists argue, can be used to simulate the beliefs/mental states of other humans by altering the inputs to our own mental architecture and then emulate what they believe by establishing what we would believe under similar circumstances. That we could believe that another person can hold a belief different to our own, and that there are things that I know that you don’t know is a complicated set of concepts, Carruthers attests that they are too complicated for FOR, therefor they are HOR, and if they are HORS, and not HOEs (as they precede them) they must be HOTs, and if a being has HOTs then why would it need HOEs? But ToM is a prerequisite for HOTs, so while HORs may not explain ToM, they’re not refuted by this argument.

As a plausible alternative story I suggest the mechanisms for self-awareness developed from the “perceptual information is made available to simple conceptual thought and reasoning” (Carruthers 2000 p257) which Carruthers accepts is a feature of higher mammals. We don’t simply ascribe intention to each other, we ascribe intension to almost anything that moves. It is not so complex a leap to hypothesise potential actions to prey animals, via visual imagination. Those that anticipate better than their peers are likely to be more successful at hunting, hence eating. An arms race that built upon predictive imagination, and social Machiavellianism could allow a slow progress to ever more complex p-consciousness where we turned the tools developed for understanding others upon ourselves, without requiring a moment of clarity.

Thereby transitioning from FORs, into HOEs, to HOTs, then HODs each adding a layer of complexity to the previous substratum in a continuous fashion.

Bibliography:

| Carruthers, P. (2000). 12 The evolution of consciousness. Evolution and the human mind: Modularity, language and meta-cognition, 254. | |

| Carruthers, P. (2003). Phenomenal consciousness: A naturalistic theory. Cambridge University Press. | |

| Völlm, B. A., Taylor, A. N., Richardson, P., Corcoran, R., Stirling, J., McKie, S & Elliott, R. (2006). Neuronal correlates of theory of mind and empathy: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study in a nonverbal task. Neuroimage,29(1), 90-98. | |

Huth, A. G., Nishimoto, S., Vu, A. T., & Gallant, J. L. (2012). A continuous semantic space describes the representation of thousands of object and action categories across the human brain. Neuron, 76(6), 1210-1224.

| Varley, R., & Siegal, M. (2000). Evidence for cognition without grammar from causal reasoning and ‘theory of mind’in an agrammatic aphasic patient. Current Biology, 10(12), 723-726. | |

Dunbar, R. I. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates.Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469-493.

Poldrack, R. A., & Farah, M. J. (2015). Progress and challenges in probing the human brain. Nature, 526(7573), 371-379.

Fig A: Völlm et al. (2006). p95

Fig B: Poldrack, & Farah (2015) p374

Fig C: Huth et al. 2012, website: http://gallantlab.org/brainviewer/huthetal2012/, accessed 18th Oct 2015