Theoretical disagreements in the domain of Social Learning

Each of the papers which I have decided to examine for this exercise consider the domain of social learning:

- “Social Learning in Complex Networks: The Role of Building Blocks and Environmental Change” by Barkoczi & Galesic presented at CogSci 2013: 35th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society

- “Understanding social learning behaviours of xMOOC completers” by Skrypnyk, Hennis, & Vries presented at the European MOOCs Stakeholders summit 2015,

- and the National Bureau of Economic Research working paper “Social Learning and Communication” by BenYishay & Mobarak

Each of these papers takes a different look at how social learning occurs and examines the mechanisms of social learning accordingly. Barkoczi and Galesic take a highly cognitive approach, considering learning as function of the structure of social networks, they compare and contrast the outcomes of different learning strategies – imitate-the-best and imitate-the-majority – within a varied set of structured social environments. Skrypnyk, Hennis, and Vries examine how the behaviours of those from a number of different cultural backgrounds amongst those people who completed certain MOOCs, and also consider how the dynamics of these learning environments have an effect upon learning outcomes. Whereas BenYishay and Mobarak focussed upon the social relationships between the teachers and the students (while also considering the structured incentives of the teachers) under field experiment conditions in sub-Saharan Africa.

Learning with building blocks:

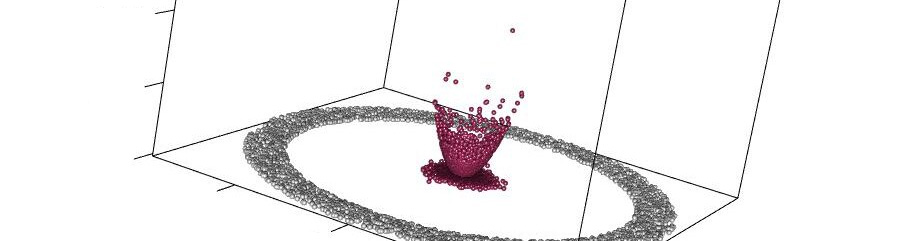

Barkoczi and Galesic approach learning under the rubric of modular conceptual processes. Each agent it their simulations may use a different strategy for learning how to use the resources which are environmentally available to it. Multiple methods are available for using the resources that the agents have available to them. Individual agents may spontaneously learn new methods independently, or conversely may learn them from their peers. Individual agents use the most effective method that they have learned. Peers know the efficacy of the methods that their peers use, by observing the results. Individual agents then choose either the method used by the majority of their peers, or the method that the most effective of their peers is using.

From the initial conditions the network stabilises to the most efficient methodology over time, the time taken to reach equilibrium is a function of the learning strategy (best vs majority) that agents employ (best is quicker).

Environmental variables change randomly, this leads to a disequilibrium, alternative methodologies disseminate across the network until a new equilibrium is reached, the dissemination of which is a function of both interconnectedness vs clustering, (where interconnectedness slows learning through the majority strategy, and maximal connectedness ensures that the dominant strategy is conserved regardless of the environmental changes) and learning strategy (whether agents use the method which most of its peers use – majority – or whether the agent uses the strategy that maximises the utility of the resources available to it –best).

This building blocks model imagines learning, even social learning, as an internally led behaviour, with this Barkoczi and Galesic lie within the Piaget school of development. If we consider their simulations from a Piagetistic perspective we can see how the processes of assimilation and accommodation emerge from within the agents that exist, embedded in their network. As the global variables (and thus the environment of the simulation) change the agents assimilate this new information and consequently accommodate their behaviour to these new circumstances (by adjusting the schema that they use either through spontaneous innovation, or some strategy of learning).

Barkoczi and Galesic use a very simplified approach to learning, for them learning is the process of dissemination of information across a network, the network moves into equilibrium states and transformations between these states occur in response to environmental changes, in this it is dynamic. Furthermore, while the experimenters do alter the structure of the network, the network is not autoregressive in the sense that it is a function of the actions of the agents, instead it is an external environmental component that is independent of the agents, and the activities of the agents.

They differ from classical conception of Piaget insofar as the agents in this model are identical, their capacities to implement new methodologies do not diverge whereas Piaget would have seen development to have been a self-directed process which is a consequence of the environmental circumstance the person learning found themselves in. In a natural environment so, every learner would have a differing set of learning needs. As a consequence of this universalism the peer relationships between agents are also identical: peer relationships are vectors of information transfer, varying only in the numbers of peer-to-peer connections, not in their capacity to convey information.

This information-transactional approach to learning taken by Barkoczi and Galesic is frictionless, noiseless and complete, it takes no effort to learn a new methodology, the behaviour and methodology of every agent is transparent to all of their peers, and it is inherently obvious to the agent what the outcome of a given strategy might be.

Education as a learner constructed environment:

In contrast, with “Understanding social learning behaviours of xMOOC completers” Skrypnyk, Hennis, & Vries consider the technological and cultural environments of the people who are learning. To this end, they examined the behaviours of those people who completed two engineering courses offered by the Delft University of Technology using the edX learning platform.

Massive Open Online Courses are of a design structure which make a lot of Piagetistic assumptions about the needs and behaviours of students. All students are self-directed insofar as they learn the things which they choose to find out about, and to a large extent depend upon cognitive constructivism to drive the acquisition of knowledge in an learning space which is isolated (in terms of direct unmediated personal interaction).

Aside from the course materials these MOOCs often come with an associated forum. The interaction that occurs within these fora can be viewed through either a Piagetistic or a Voygotskian frame of reference. While the Piagetistic perspective of interaction through learning is one of individuals discovering error through argumentation, the social-cultural perspective of Voygotsky has many other mechanisms.

A principle of Voygorsky’s view is that we can perform more complicated tasks when we are helped by people who are more sophisticated in that area: Just as parents can stretch their children to find new limits to their abilities, then so can we all. The framework of the zone of proximal development suggest that our learning opportunities are contingent upon our previous knowledge and the guidance available to us, and learning occurs at the boundary of our competence.

A feature of MOOCs is their very high rates of attrition, Coursera averages about a 4% completion rate, Harvard’s courses on edX have a 6% completion rate. The Water and Solar courses offered by Delft has completion rates of 2% and 5% with 25,000 and 60,000 people signing up to these courses, respectively.

Given the numbers involved, where courses that have 98% drop out rates still have hundreds of people completing these courses, it would be impossible for any one educator to support the learning needs of all these students, consequently this learning support has to be peer mediated in the MOOC environment.

Through this lens, the forum elements of MOOCs need not be disputative to be useful. They can provide learning opportunities through being collaborative. While MOOCs are cognitively challenging tasks that allow us to go beyond the synthesis of self and course material, using mechanisms like social activities they should also allow students to “benefit from the collaboration and interaction undertaken with peers” (O’Donnell et al. 2015 p102).

Skrypnyk, Hennis, and Vries have found elements which suggest that cultural mediation may be a factor among those who have completed the courses which they examined.

Skrypnyk, Hennis, and Vries (2014)

Among those who completed the courses there is a high degree of inter-cultural variation, accompanied by a low degree of inter-course variation is the patterns of forum use that the students engaged in.

Two other important observations made by the Delft team were with regard to the structure of these social learning environment. Different patterns of teacher engagement with the fora had students competing (or not) for status and attention from the teachers. Meanwhile for others among the students that completed the WaterX course, the forum attached to the course did not meet their needs and so they created their own parallel environment through using Facebook.

Thus we see a view of learning which can also be a form of social behaviour, and one which has a variety of social and cultural complexities inherent to it that would not be observable unless one avoided the Piagetistic viewpoint. Here we have a view of social learning which moves beyond the simple transfer of information and shows that the learning environment can be more than simply a constraint upon the system, it can also be a dynamic and responsive element in the learning, allowing for the construction of novel social networks, and new paths to learning.

Clearly not all people require that such environments need to be created. Approximately half of those who completed these courses were self-directed. But overall, the researchers found “that social interaction with other learners is beneficial for student performance, but that forum strategies and platform affordances create unequal opportunities for participation, as MOOC learners are diverse and their needs differ” thus the constraints imposed by the cultural environments from which the participants emerge are vital aspects of any examination of a social learning environment, as too is the structure of the social learning environment. This suggests that we should be conservative with it comes to the universalisation of results which emerge from social learning studies.

Education mediated through relationships

The third paper that I look at is “Social Learning and Communication” by BenYishay and Mobarak where the researchers conducted a randomised controlled trial, with three arms to it, seeking to establish how different types of teachers, and the incentives under which these teachers worked, facilitated or hindered social learning.

The experiment looked at farmer education programmes in sub-Saharan Africa, with the experiment occurring in Malawi. The principle concern of the experimenters was how to improve the farming techniques among this population. Despite the fact that considerable efforts, resources, money and time have gone into farmer education programs “agricultural yields and productivity have remained low and flat in sub-Saharan Africa over the last 40 years”. The intuition of the researchers was that because “[e]xisting models of passive social learning ignore communication (since agents automatically observe neighbors’ actions)” they do not capture important elements of the process of social learning. These gaps may have an explanatory part in the “information failures” which have stymied the transmission of new farming techniques among sub-Saharan farmers.

The frictionless information model which Barkoczi and Galesic for social learning has great problems when it abuts against reality. Change carries costs, and carries risks. If you are a Malawian farmer, do you trust a civil servant to give you credible information about what crops to grow? Does this person know what the soil conditions in your area? Are they taking a bribe from a company that is supplying the seed? Have they ever farmed? If they did farm have they ever farmed crops like you have? Because the Malawian farmers have survived up until this point, then what they have been doing has been sufficient to survive under the local circumstances, there is an obvious risk attached to changing this behaviour. Furthermore new crops could require new skills which may make for leaner years before full production is possible, so even if things may be better in the long run, you might starve before that day arrives.

Consequently the agent in real life has to be able to assess the quality of the information that is being made available to them, and also the reliability of the person who is communicating it. The experimenters considered three models for communicating this new information. The first was an appeal to an expert, or outside authority, the second was an appeal to a role model or local social leader, and the third was another farmer of the same social standing with a comparable farm.

As a consequence of this research BenYishay and Mobarak established that the Malawian farmers used the identity of the teacher as a proxy for their reliability. Where a famer knew that the person they were talking to was a farmer of a similar background, who had a farm similar to theirs, only then were they willing to learn from that other farmer. A further complication was that while learning new skills can have uncertain costs, teaching these same skills to other people has definite costs (as a consequence of the time spent trying to teach this new information to the other farmer). As a consequence it was not sufficient to teach certain farmers new skills and then wait for this information to permeate the local community (which is exactly what the Barkoczi and Galesic model assumes to occur) it was necessary to alter the behaviour, through incentives, the people who invest their time educating others. To resolve this part of the problem the researchers paid (with bags of seed) peer-teaching farmers to train other farmers up in these new skills, thereby subsidising the transactional costs of communication.

This relationship-modulated approach to social learning is more Voygorskian than Piagetistic emphasising how, even in a homogenous culture, interpersonal factors systematically effect behaviours and learning outcomes.

Juxtaposing BenYishay and Mobarak’s research on sub-Saharan farmers against Skrypnyk, Hennis, and Vries’s work on MOOCs we can see how these may be able to inform each other. There is the risk of overgeneralising the work of BenYishay and Mobarak, it seems to have robust results within the environment and culture where the experiment was carried out, but it may not be wise to assume that the same techniques will be as effective within a population of New Zealand sheep herders, or Afghan poppy farmers.

Transposing BenYishay and Mobarak’s work into the world of MOOCs we can see how ineffectual the assumption of frictionless, transparent transmission of information may be. Huge resources have been put into re-educating sub-Saharan farmers in their techniques, to no purposeful effect. This presents itself as a huge opportunity cost, both in terms of the resources applied to the problem, and the relative prosperity which these same farmers have missed out on. Costs which are a consequence of poorly applied social learning theories.

We can see something similar occurring with Universities and MOOCs. MOOCs are created to be used by the solo mind where the student completes a series of practical activities which are designed to extend the set of information available to the student’s mind. This is a model which is useful to some people, a set of people whose proportion of the interested population seems to be in the low single digit percentages. If we are to assume that learning does not stop at maturity, as Piaget would have it, and continues as a life-long process then we’ve to carefully assess the structures of the learning environment, and the dynamics of the relationships that govern the learning environment. In a few short years MOOCs have changed from being a new potentially revolutionary form of educational resource, to being a form of marketing that aims to attract foreign students to top tier universities. There is the potential for a great opportunity cost of poorly implementing novel learning technologies such as MOOCs simply because most of them seem to be little more than an undergraduate course that is recorded to video and uploaded to the internet.

In contrast, the risk of over-prescribing the Voygorskian theory is that it is useful for dealing with solved problems. In environments that require novel solutions, or where there is limited existing expertise, the introspective mechanisms of Piaget may be all that is available. Too much social scaffolding can be limiting if we don’t also learn ways to extend beyond its confines.

The key feature of social learning is that it is complicated, it features complicated people, operating within the bounds of complicated cultural constraints, limited by a complicated dynamic environment, trying to solve complicated problems. Such complex scenarios are not pliable to silver bullets, typically resolving them will require the development of tailored well-fitting solutions. Such solutions necessitate learning skills that help us learn broadly, learn deeply, and learn to appreciate the rich web of connections that link the diverse aspects of our knowledge.