The Zollvererin roots of Germany’s sovereign power grab

When we try to understand the actions of Germany, with respect to the Eurozone, we have to look first at the Zollvererin league.

When we try to understand the actions of Germany, with respect to the Eurozone, we have to look first at the Zollvererin league.

The Zollvererin was a stepping stone to a united Germany, and it is supposed that the Euro will be the bridge that leads to a united Europe (why else are there imaginary bridges on the notes).

But the logic immediately breaks down there. The Zollvererin was a currency which united the disparate Germanic states, of what had been the core of the Holy Roman Empire, after the excesses of Napoleon. But they were relatively homogeneous (certainly compared to the EU of today) and they were facing an existential threat (they couldn’t know that French imperial power was sundered at that stage) so first they united in commerce, and then ultimately in war (under Bismark against the French).

There is a large degree of myth making in the foundation tales of any nation, for Germany the primary myth it is the inevitability of Germany. There were epochs where events got in the way of a united Germany but there is a definite sense that regardless of all hindrances Germany would be one. So Germany became one again to crush the French (rather than say, wily politicians used the war to allow Prussia to dominate central Europe).

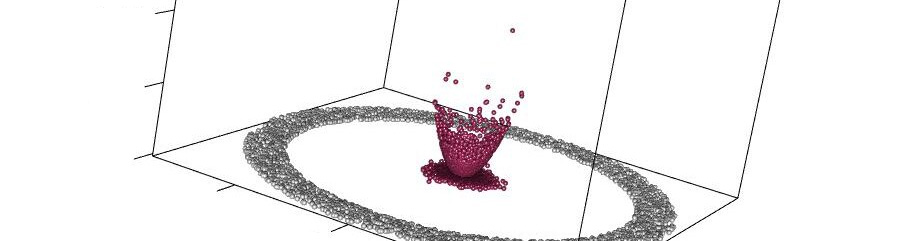

If you approach it from the perspective that there was a natural progression towards Germany, much as water flows towards the sea, then the Zollvererin was a vital prerequisite of the united Germany (as it allowed links of commerce and culture to be forged under the protection of this initially international institution, which became ultimately federal, albeit is some detours in between).

It is almost as if, given that the Zollvererin facilitated the inevitable, then the Zollvererin must have been a necessary precondition to the united Germany; which is of course a logical fallacy.

But that is what Claude Levy-Strauss argues myths are for, to hide our internal contradictions, the conquering of cognitive dissonance.

This myth also fails to note that most currency unions end in failure, so it is not sufficient precondition for political union.

Compounding this, there is the German tendency towards Hegelianism, that conflation of what is rational, with what is moral. The Germans have never been a logical people, but the see themselves as so, and therefore make the mistakes of the fundamentalist; they confuse believing that they are correct in thought and action with “right”, and so introduce the false dichotomy that those who disagree with them are either stupid or clever (but corrupt).