The normative source of Autonomy

In Korsgaards’s “The Sources of Normativity” she makes the case that in modern moral philosophy the challenge has been to ground the ought; if morality argues that we ought to behave a certain way, then what is it about the nature of morality that it can command our behaviour? If Grotius is right and there is no God, or at least there is no God that concerns itself with the affairs of men, then if we are to have a morality, it cannot be a morality that has recourse to the prescriptions and proscriptions of a God.

Korsgaard outlines four broad threads of thinking that have attempted to find an immovable point to which the problem of morality can be tied. For the Voluntarists it is the collective decision to enter into a combine with our fellows. Though this compact, the sovereign is imbued with the capacity to punish, allowing the Sovereign to do harm, though legitimately, to any of those who do not abide by the laws. It is this entry into the community of our fellow humans that the Voluntarists affix the framework of Morality.

In contrast to this, what Korsgaard calls the “Reflective Endorsement” view “grounds morality in human dispositions”, that there is a kindness inherent in the human sentiments which allows us to disapprove of the wrong, and so this aesthetic approach to morality signals to us that which is right, and that which is wrong. Furthermore, those who do right, are right, and those that do wrong, are wrong. Society then acts upon artificial virtues that require duties of us, wherein we find ourselves under imperfect obligations to behave in particular ways. That this remains an aesthetic choice, is a function of how we feel about doing things that ought not be done. It is the unpleasantness of the feeling that others may discover the unacceptable aspects of our behaviour that signals to us the deviance of our behaviour. If we do that which is pleasant, and avoid doing that which is unpleasant then this form of self-interested behaviour will guide us through these thickets of the wrongs and the rights.

Contrasting with this subjective view of morality, is the realist position that would contest that it is not in the self that we establish the rightness or wrongness of a deed, the rightness or wrongness lies in the deed itself, there are things that are right, and things that are wrong, that rightness or wrongness is not a consequence of our reaction to the deed (Hume’s immorality of murder because it’s viciousness displeases us, is incorrect, murder is immoral because it is immoral). The position for the realist is almost to deny the normative question, there is no reason to question why we should do, or not do, a deed; the rightness, or otherwise, of the deed is a fact of nature, a consequence of reality.

Finally we have the “Appeal to Autonomy”, the claim that there is a special form of being which is defining of ourselves which allows us an engagement with the universal through the practice of reason. The appeal to Autonomy finds the self’s government of the self to be the source of the moral law that with which we bind our behaviour. We can, through the skilled application of reason, transcend the merely good (the self-interested goals and deeds of those who would recommend that which they would grant their subjective “Reflective Endorsement”) and so elicit a moral law that we know to be right, because it is rational. If it is rational then all people could see it to be both rational and right, therefore if all were rational, then all would behave in concordance, and so we would have access to a universal obligation that is derived from the self that is alienated from self-interest.

Conflict as the source of a sense of Morality:

There is a sense at the heart of the normative question that it is also a rejection of the deterministic universe. As much as the question is “Why should we do right?” the question is also “Why should we not do wrong?”. The intuition being that in the state of nature, our inclinations would first be to do wrong, and that it is only in reaction to some extra-natural (something beyond the merely animal) impulse that we would discover the possibility of doing right. This is a rejection of the deterministic universe insofar as it presupposes that we do have a choice when it comes to our deeds. The second implication of this intuition is that we operate our choices within a framework of conflict and competing interests.

Our moral moments are reactions to circumstances; there exists those moments where we have the opportunity to make a decision, where we are presented with a set of potentialities, and where some of those potentialities can be accessed more easily than others, and yet we feel a sense that we ought to not take that option which would otherwise come most easily. That there is instead a right choice. A right choice where, despite it being difficult, it is the choice that a right thinking person takes.

No other choice is a choice where morality is a concern. If the right runs in concourse with the easy, when there is not even a choice to be made, as water flows down a hillside we take that course that is less difficult – it would take a particularly perverse mind to know that the right is the easy, and yet do harm, even though the harm is the harder course to take.

Korgaard argues that “the day will come, for most of us, when what morality commands, obliges, or recommends is hard” (2008:22). A concern that I have with this view is that it necessitates that there will be circumstances where morality must also command us to also take that action which is easy, and so that there is no special feature of morality which distinguishes the moral action, from any other action. By extending morality beyond those circumstances where it is hard, where morality extends into choices and decisions where we are not challenged to take, then we have a morality that is spread so thinly it becomes transparent.

The Domain of the Moral Choice:

We should take a moment to consider what is necessary for someone to behave in a perversely harmful way. There are right deeds where some other person will receive some kind of benefit as a consequence of our action. There are neutral deeds where no one will receive a benefit, and also no one will be harmed as a consequence of the action. There are some kind of deeds where a person will be harmed as a consequence of the action. Finally, there are those other deeds where there will be some complex combination of the beneficial and the harmful.

If a deed is neutral, it should not be considered within the frame of morality. If a deed is both right and easy, then to do otherwise is to do a harm to oneself and would suggest a kind of gross misalignment of personality that would approach madness.

There are deeds where harm is done, and good is done, and where an individual must choose between different possible potential actions, and also where that individual believes that there are competing obligations acting on them, otherwise there is no choice involved: This is the domain of moral choice.

The defining aspect of the moral is, I claim, that it is a challenge to the self. It arises not simply because there is a normative claim upon me that I must take a particular action, but that I must take that particular action in contravention of some other normative claim upon my self, otherwise there is no choice to be made.

The role of Autonomy in the domain of moral choice:

As Korsgaard notes, it is in reaction to “The Modern Scientific World View” that we have had to develop the concept of autonomy. Absent a sovereign god that compels us to behave in certain ways, then where does this sense of moral obligation derive from? For Hobbes, they derive as a consequence of that sovereign individual who can punish us if our actions contradict certain universal laws, whose powers of compulsion derive from a social contract that is entered into as part of a universal compact. The response to this form of thought was to query as to why we would be obliged to follow such a compact? Which raises the threat of an infinite regress for those of the Volunterist position, a regress that the Realists avoid through the statement that “it is”.

Kant’s solution to this was the transcendental claims caused by the “Appeal to Autonomy”; that as we are self-sovereign through reason, and therefore we can act in accordance with those maxims which we can wish should become a universal law, then we can imagine a world were all people would act in a particular way (without regard for what is good for them personally), then that way that they would act, in this “Kingdom of Ends” is the moral way, where pure reason determines the choices and wishes of every individual.

For Kant, the claim of normativity has to reside in the self, in the free will. This free will has an ultimate form of agency, insofar as it can act, but it cannot be acted upon, except upon itself. This will can act even upon its own faculty of desire, determining not only what it wills to be, but also what it would wish would be willed to be.

The journey towards a normative cause for moral choice requires for Kant a series of reifications which ultimately requires the fashioning of a unique place for humanity in the universe. This specialness of humanity is a result of our access to the Categorical Imperative which is accessible though our will, in turn “a good will is a will whose decisions are wholly determined by moral demands or as he often refers to this, by the Moral Law” (Johnson, 2008).

Autonomy as a denial of the good:

This is possible for Kant only because he denies the good, or at least he denies the self-interested. Kant did allow that human choice is muddied and imperfect, but his argument from here was therefore that the muddied and the human was irrelevant to the moral:

Thus not only are moral laws together with their principles essentially distinguished among all practical cognition from everything else in which there is anything empirical, but all moral philosophy rests entirely on its pure part, and when applied to the human being it borrows not the least bit from knowledge about him (anthropology), but it gives him as a rational being laws a priori, which to be sure require a power of judgment sharpened through experience, partly to distinguish in which cases they have their application, and partly to obtain access for them to the will of the human being and emphasis for their fulfilment, since he, as affected with so many inclinations, is susceptible to the idea of a pure practical reason, but is not so easily capable of making it effective in concreto in his course of life.

(Kant, 2002:24, Ak 4:389)

In reaction to the excising of God from morality, Kant found it necessary to excise the human from morality too, in doing so, recognising that the morality prescribed was a morality that was alienated from humanity. For such a morality to exist, then pure practical reason must be attainable. Conversely if pure practical reasoning is unattainable, or if it may be seen to be unattainable, then the universalism of the moral law is under threat, and Kant’s moral scheme collapses back into the subjectivism of the self-interested Subjective-Endorsers. Sadly, for Kant’s position there is much evidence to show that we are weakly reasoning creatures. While accepting of this impurity in our reasoning, Kant still claims that somewhere beyond us, there is a moral way of being that has claims upon us, because it is right. Yet we might not be able to distinguish it from any other set of claims to the moral right that our impure reasoning might derive.

Kant’s Autonomy requires a kind of godliness about ourselves: To create a normative necessity to behave in a moral way in the absence of God, Kant requires us to transcend to a form of Godhood ourselves, including a maximally extended form of Autonomy; resolving the problem of normativity for an autonomous being, by creating the reversal of our normative obligations as an inevitable consequence of our Autonomy. Kant’s Autonomy is the Autonomy of a transcendental god, a god that does not involve itself in the affairs of mankind. It is also a brittle, crystalline form of Autonomy; it is absolute in its prescriptions, and so denies the capacity for freedom of action. If ever our reason is flawed, and if ever our subjectivity slips into our considerations, and if as Kant claims that only the self may act on the self, then we might commit every kind of wrong, while believing we are right. Never knowing our error, we can create an Ideal of an Ideology; the most traditional route being to deny another their full membership of ‘humanity’.

Freedom from Autonomy:

Is there an escape from Kant’s frozen, glaciated berg of Autonomy which denies our selves, and limits our actions to the perfect? I think there might be, but only at the price of sacrificing the absolute. Kant’s form of Autonomy is a requirement of avoiding the infinite regressions of the Voluntarists. But this critique of the Voluntarists is a consequence of an implicit belief in our Autonomy. It pre-supposes (as too do the voluntarists themselves) that humans had existed in a state of nature where once we have an autonomy. If we had Autonomy, then what presaged the transition into barbarism? A state of nature with Autonomous beings would be the Kingdom of Ends itself, and if this Eden had existed, then where did these competing claims upon my self emerge from? But had there been claims upon my self, even in this state of nature, then from whence did they derive? And so it seems that we enter the enter the problem of infinite regress, except of course that neither time, nor humanity is infinite.

Humanity as we are today, did not spring into being de novo, it emerged from a muddy, messy hybridisation of related species, all of which contained communities, and cultures. Modern humans are the hybrids of homo-sapiens, and also separate species including Neanderthals, Devonisians (Huerta-Sánchez et al. 2014, Marchi et al. 2013, Lee et al. 2014, Alves et al. 2012), and possibly other early humans, these sister species have left a genetic heritage in modern human populations through cross-breeding with us, they too had the anatomical features associated with speech, and had the musical instruments and tools that accompany culture in ways that we are familiar with.

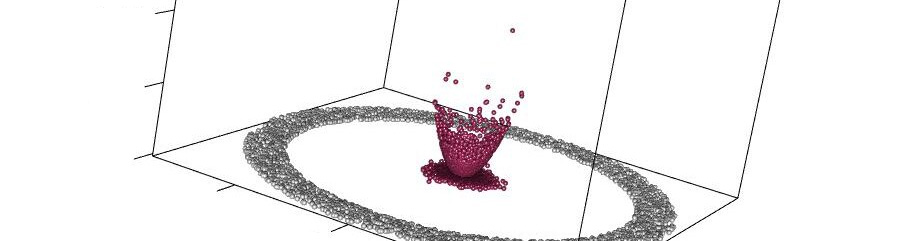

These sister species diverged from our common ancestors in a time long before modern humans evolved, showing that culture and community preceded the existence of humans, as we have come to know ourselves. If we recall my claim regarding the essential components of a moral choice, namely the competition of interests (for oneself, and others, or particular groups of others) and consider how these competing drives play out in an evolutionary context, under natural selection. The tension between the obligations to oneself, and the obligations towards others, which I believe to be the hallmark of a moral quandary, can aid the expansion of activities in a dynamic environment, where either of the fixed alternative interests may fail as a strategy, as environmental niches change: This contradiction of interests allows there to be different possible solutions to different sets of problems.

Then if, our communities, and our obligations to each other, extend in time to back before what we now recognise as human then we can see how evolution can solve an aspect of the infinite regression challenge. While closer to the subjective self-interested models of aesthetic morality, if we consider the bottleneck of evolution, and how it can cull strategies which are not successful, then it allows us to satisfy the realists in terms of these strategies having a co-joint, though only coincidentally necessary relationship with modern humans. This deep history allows for enculturation and biology to act on us through mechanisms familiar to us and the reflective-endorsers, while the maintenance of a limited autonomy allows us, as a species, to innovate strategies according to the appropriateness of the occasion.

This, I believe, marries the claims of the realists, the voluntarists and the reflective-endorsers, while keeping open a role for a more limited, more human, autonomy, though at the cost of an absolute morality.

Bibliography:

Alves, I., Hanulová, A. Š., Foll, M., & Excoffier, L. (2012). Genomic data reveal a complex making of humans. PLoS Genet, 8(7), e1002837.

Huerta-Sánchez, E., Jin, X., Bianba, Z., Peter, B. M., Vinckenbosch, N., Liang, Y., … & Wang, B. (2014). Altitude adaptation in Tibetans caused by introgression of Denisovan-like DNA. Nature, 512(7513), 194-197.

Johnson, R. (2008). Kant’s moral philosophy. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy.

Kant, I., Wood, A. W., & Schneewind, J. B. (2002). Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals. Yale University Press.

Korsgaard, C. M., & O’Neill, O. (1996). The sources of normativity. Cambridge University Press.

Lee, A., Huntley, D., Aiewsakun, P., Kanda, R. K., Lynn, C., & Tristem, M. (2014). Novel Denisovan and Neanderthal Retroviruses. Journal of virology, 88(21), 12907-12909.

Marchi, E., Kanapin, A., Byott, M., Magiorkinis, G., & Belshaw, R. (2013). Neanderthal and Denisovan retroviruses in modern humans. Current Biology, 23(22), R994-R995.